CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 2, March/April 2015

60

AFRICA

Table 3 shows means (SD) and medians (25th and 75th

percentiles) of urine volume, urinary sodium, urinary potassium

and salt intake, according to gender. Compared to women,

men had significantly higher mean values for urine volume and

sodium-to-potassium ratio. There was no statistically significant

difference between men and women for urinary sodium and

potassium concentration and daily salt intake. The proportion of

participants exceeding the limit of 5 g/day of salt in the overall

population was 96.7%, without a gender difference.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine salt intake so as to

assess the knowledge, attitude and behaviour regarding dietary

salt in a representative sample of medical students. The main

findings were a high average daily salt intake and inadequate

behaviour regarding dietary salt consumption in the majority of

participants.

The level of salt intake seen in this study was more than

two-fold the maximum internationally recommended limit,

7

indicating a salt-rich diet consumed by our participants. This

finding corroborates with that reported for the general population

worldwide.

7,17,19

Despite the known relationship between salt

intake and blood pressure levels, data on salt consumption based

on properly collected 24-hour urine samples are lacking for

young medical students.

Participants for this study were randomly selected from a

population of medical students and we used the ‘gold-standard’

24-hour urine method to assess salt intake. Their knowledge,

behaviour and attitudes on dietary salt intake were also assessed

using a standardised WHO questionnaire.

24

Salt intake was estimated using sodium concentration in

24-hour urine samples, and checks for completeness of 24-hour

urine collection were based on a combination of self-reported

urine loss, 24-hour urine volume measured at the laboratory, and

the recorded timing of urine collection. These criteria enabled us

to exclude 15% of the urine samples assumed to be incomplete

collections for the 24-hour period, with the majority of them

excluded due to incomplete timing of the urine collection.

The validated urine samples were therefore 80.4% of the total

collected.

Identifying the main source of dietary salt is important to

control high salt intake in the population. Therefore, behavioural

change in the use of salt is one of the strategies recommended

to reduce high salt intake in contexts where most sodium intake

comes from salt added during cooking or at the table at home.

7

From the survey, we found that almost all our participants

were aware of the health consequences of a high-salt diet, and

reported more frequently eating food with salt added during

cooking in their homes, and less frequently eating food with salt

added at the table. However, less than half the total participants

reported being aware of their high sodium intake, and the

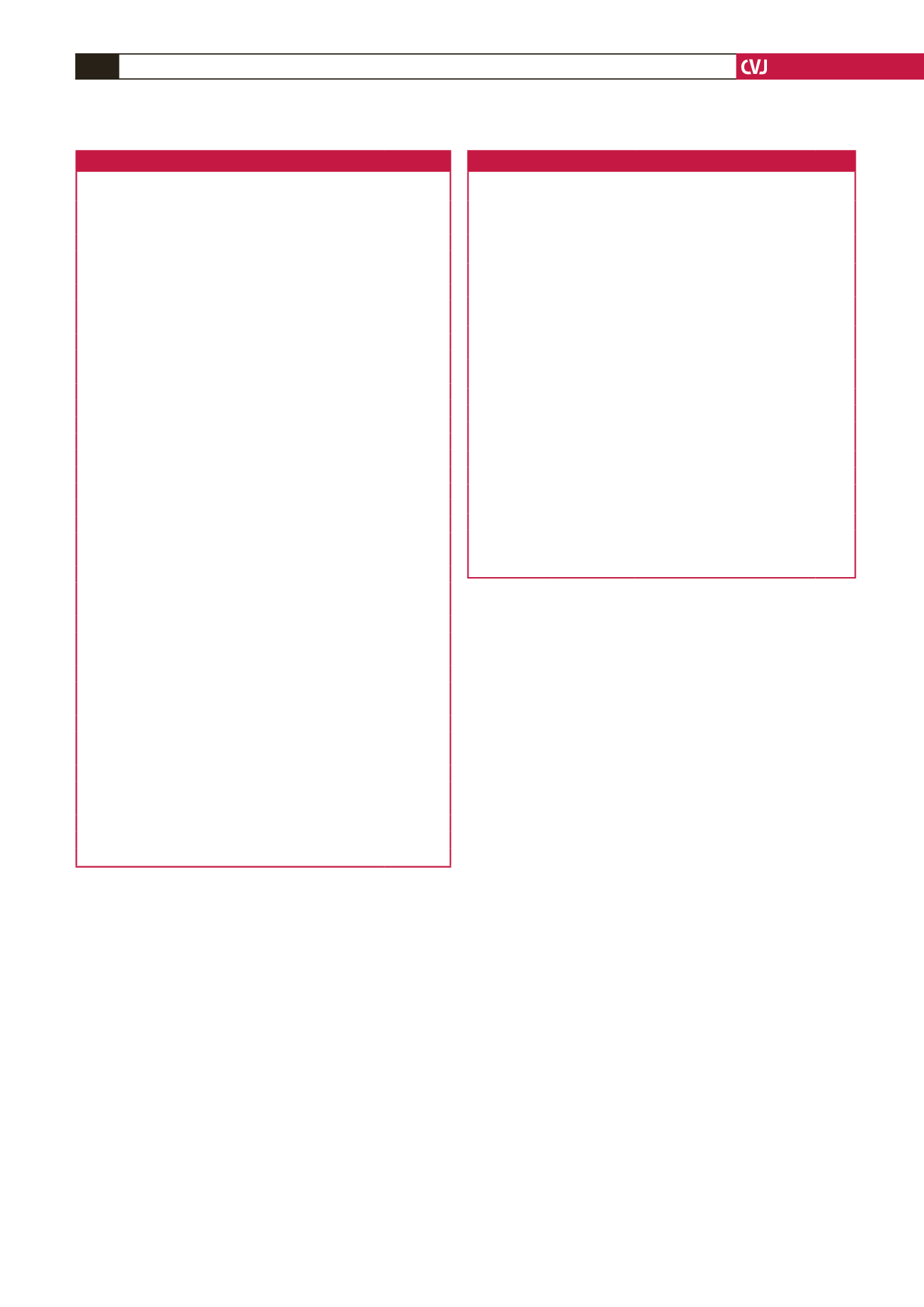

Table 2. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour on dietary salt

Question

Total

n

(%)

Is salt added in cooking the food that you eat at the home?

Never

0 (0.0)

Rarely

1 (0.8)

Sometimes

0 (0.0)

Often

19 (15.4)

Always

103 (83.7)

How much salt do you think you consume?

Far too much

4 (3.3)

Too much

4 (3.3)

Just the right amount

69 (56.1)

Too little

31 (25.2)

Far too little

2 (1.6)

Don’t know

13 (10.6)

Do you add salt to food at the table?

Never

30 (24.4)

Rarely

46 (37.4)

Sometimes

40 (32.5)

Often

2 (1.6)

Always

5 (4.1)

Do you think that a high-salt diet could cause a health problem?

Yes

122 (99.2)

No

0 (0.0)

Don’t know

1 (0.8)

How important to you is lowering the salt/sodium in your diet?

Not at all important

2 (1.6)

Somewhat important

9 (7.3)

Very important

112 (91.1)

Do you do anything to control your salt or sodium intake?

Yes

56 (45.5)

No

63 (51.2)

Don’t know

4 (3.3)

If answered ‘yes’, what do you do to control your salt intake?

Avoid/minimise consumption of processed foods

4 (7.1)

Look at the salt or sodium labels on food

0 (0.0)

Do not add salt at the table

47 (83.9)

Buy low-salt alternatives

2 (3.6)

Buy low-sodium alternatives

1 (1.8)

Do not add salt when cooking

1 (1.8)

Use spices other than salt when cooking

0 (0.0)

Avoid eating out

1 (1.8)

Table 3. Mean and median values of urinary data according to gender

Variables

All

(

n

=

123)

Men

(

n

=

54)

Women

(

n

=

69)

p

-value

Urine volume (ml/d)

Mean

±

SD

1429.7

±

649.0 1579.0

±

738.5 1312.8

±

546.7 0.023

Median

(25th, 75th pc) 1320 (900, 1800) 1443.5 (915, 2152.5) 1250 (870, 1645)

U Na (mmol/l)

Mean

±

SD

94.8

±

34.4

99.2

±

37.4

91.3

±

31.7 0.221

Median

(25th, 75th pc) 95.2 (65.1, 116.0) 102.8 (63.7, 122.3) 92.6 (66.7, 113.8)

U K (mmol/l)

Mean

±

SD

33.9

±

13.6

33.0

±

15.9

34.7

±

11.6 0.496

Median

(25th, 75th pc) 33.3 (24.9, 42.9) 29.0 (22.0, 39.4) 34.7 (25.4, 43.5)

Na:K ratio

Mean

±

SD

3.0

±

1.2

3.3

±

1.3

2.8

±

1.0

0.029

Median

(25th, 75th pc) 2.7 (2.2, 3.5)

2.8 (2.3, 4.0)

2.7 (2.1, 3.3)

Salt intake (g/d)

Mean

±

SD

14.2

±

5.1

14.8

±

5.6

13.7

±

4.7

0.221

Median

(25th, 75th pc) 14.2 (9.7, 17.3)

15.4 (9.5, 18.3)

13.8 (10.0, 17.0)

High salt intake

(> 5 g/d),

n

(%)

119 (96.7)

53 (98.1)

66 (95.7)

0.439

SD, standard deviation; U Na, urinary sodium; U K, urinary potassium; Na:K,

sodium-to-potassium ratio; 25th, 75th pc, 25th and 75th percentiles.