CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 2, March 2013

38

AFRICA

countries except in South Africa and Namibia, where smoking

prevalence among women was 5.5 and 5.9%, respectively.

34

Various estimates of smoking prevalence in African men

between 1976 and 2005 revealed rates below 10% in many

African countries. But in Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa,

Mauritius and Seychelles, smoking prevalence rates ranged

between 15 and 30%. Smoking prevalence rates in adults

increased substantially across SSA by 2009, especially in

Mauritius where a third of adults smoked, closely followed by

South Africa, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Senegal with smoking

rates of 27.5, 27.1, 22.0 and 19.8%, respectively. Even in Nigeria

and Ghana, where smoking rates were relatively low before

2003, estimated at 6.1% in Nigerian men, 0.1% in Nigerian

women, 4.6% in Ghanaian men and 0.2% among Ghanaian

women, overall smoking prevalence more than doubled in men

to 13 and 10.2% in Nigeria and Ghana, respectively in 2009 but

remained quite low in women.

Although deaths from tobacco-related causes probably

accounted for only 5 to 7% in African men and 1 to 2% in

African women in the year 2000,

34

by 2030, tobacco is expected

to be the greatest contributor of deaths in SSA. Most victims will

die 20 to 25 years prematurely of various cancers, respiratory

diseases, IHD and other circulatory disorders.

Regrettably, most governments in African countries have

avoided action to control smoking for fear of harmful economic

consequences on their fragile economies. Without effective

tobacco-control measures, SSA risks becoming the biggest

global ashtray as many transnational tobacco companies shift

their targets to middle- and low-income countries.

Dyslipidaemia

There is overwhelming epidemiological evidence implicating

cholesterol as a cause of atherosclerosis. Most black Africans

reportedly have low levels of total cholesterol associated with

high high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels.

35

Higher

cholesterol levels however, have been found in diabetic patients

from Zimbabwe and Tanzania. The total serum cholesterol was

also significantly higher in women than men. Reports from

West Africa indicate a worrying trend of dyslipidaemia among

patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

36

Data

from the Transition of Health during Urbanisation of South

Africa (THUSA) study indicate that black South Africans may

be protected from IHD because of favourable lipid profiles

characterised by low total cholesterol and high HDL cholesterol

levels.

37

In Nigeria, IHD contributes very little to mortality rates in

middle-aged men and women, partly because of particularly low

mean cholesterol levels.

38

Different black African communities

may be at different stages of their epidemiological transition,

as shown in an epidemiological study of coronary heart disease

risk factors in the Orange Free State in South Africa.

39

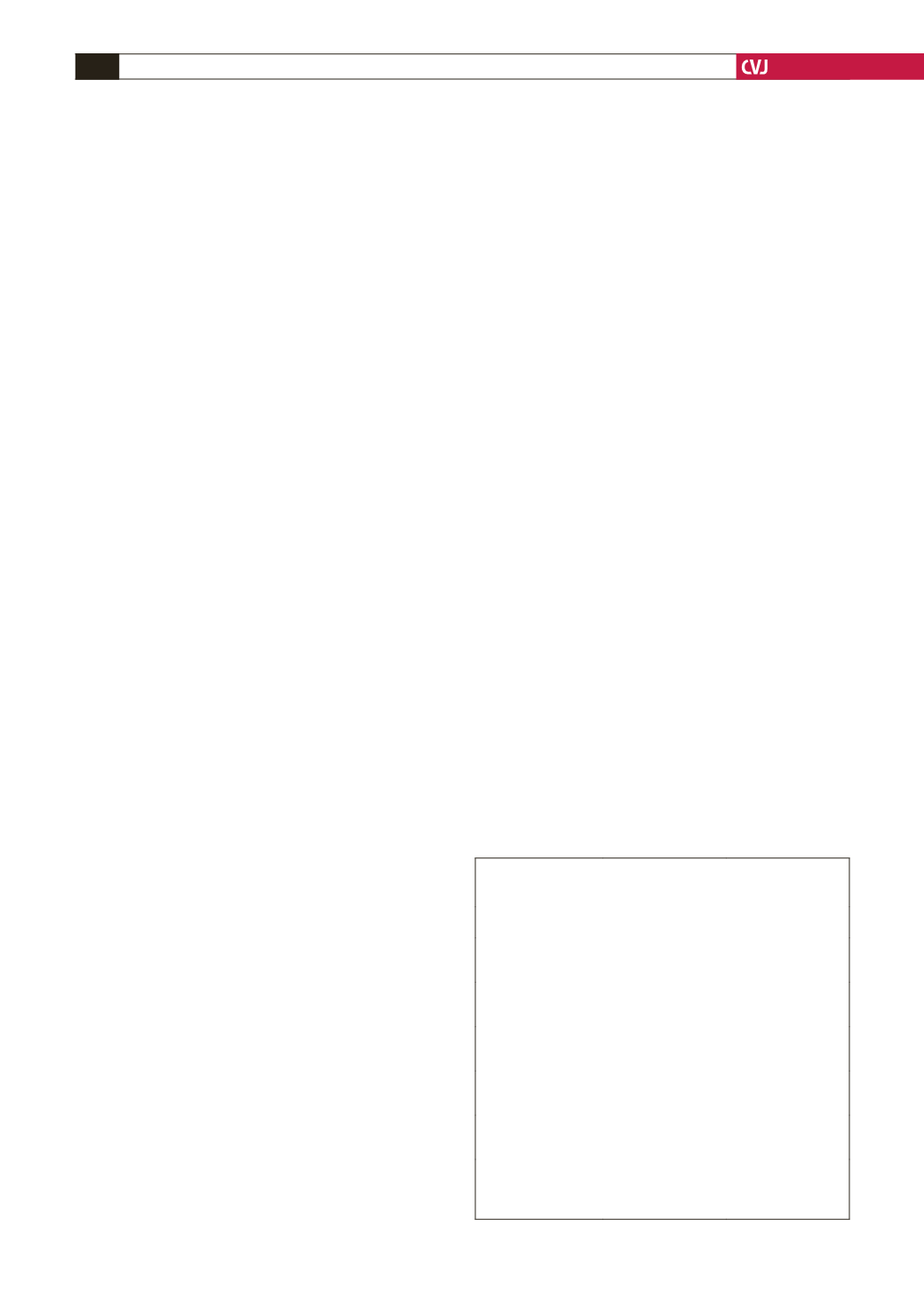

Table 4

illustrates this point quite vividly. Selected countries representing

the different regions of SSA show wide differences in mean total

cholesterol levels with a tendency to higher cholesterol levels in

females in some countries.

The cardiovascular impact of HIV/AIDS

SSA bears a disproportionate share of the global HIV burden. The

interaction between HIV infection, acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome (AIDS), its treatment with highly active antiretroviral

drugs (HAART), and cardiovascular disorders is complex and

incompletely understood.

The transformation of HIV/AIDS into a chronic disorder

with the advent of antiretroviral drugs is associated with

the emergence of certain characteristic cardiovascular risk

factors, and raises apprehension about the potential increase in

prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, including IHD, in SSA.

In Botswana, for instance, where antiretroviral therapy coverage

exceeds 90%, AIDS-related deaths declined by approximately

50% between 2002 and 2009.

40

The repertoire of immunological responses associated with

acute and chronic HIV infection is quite complex and will be only

highlighted here. Perturbations of cytokine expression, cellular

dysfunctions, redistribution of lymphocyte sub-populations,

increased cellular turnover and apoptosis are some of the

features of general activation of the host’s immune system that

characterise chronic HIV infection.

41

Chronic HIV infection, and

not its pharmacological treatment, induces changes in markers of

endothelial function.

42

Untreated HIV infection is also associated

with impaired elasticity of both large and small arteries.

43

Some authors have suggested that HIV infection accelerates

atherosclerosis via a pro-inflammatory effect on the endothelial

cells through the effects of various cytokines, especially

interleukin-6 and D-dimers.

44,45

Other mechanisms of arteriopathy

include the direct toxic effects of HIV-associated g1p20 and tat

proteins on vascular or cardiac cells. There is also evidence of

a hypercoagulable state, which inversely correlates with CD

4

count.

46

Although traditional risk factors for cardiovascular diseases

might overshadow the role of non-traditional risk factors, there

is increasing evidence that young, asymptomatic, HIV-infected

men with long-standing HIV disease demonstrate an increased

prevalence and degree of coronary atherosclerosis compared

with non-HIV-infected patients.

47

Furthermore, HIV-infected

patients tend to develop perturbations in lipid metabolism,

characterised by decreased HDL cholesterol and low-density

lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, followed by an increase in

TABLE 4. ESTIMATED MEAN TOTAL CHOLESTEROL IN

SELECTEDAFRICAN COUNTRIES BY REGION IN FEMALESAND

MALESAGED 15YEARSAND OLDER, 2011

Region/country

Females mean total

cholesterol (mmol/l)

Males mean total

cholesterol (mmol/l)

Eastern Africa

Uganda

UR Tanzania

4.4

5.2

4.7

4.4

Central Africa

DR Congo

Rwanda

4.3

4.3

4.3

4.3

Western Africa

Nigeria

Ghana

3.7

5.9

3.6

4.4

Southern Africa

Botswana

South Africa

4.7

4.4

4.7

4.4

Islands

Mauritius

Seychelles

5.2

5.9

5.2

5.8

DR Congo = Democratic Republic of Congo, UR Tanzania = United Republic

of Tanzania.

Source:

https://apps.who.int/infobase/Comparisons.aspxAccessed on 31

December 2011.