CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 2, March 2013

e8

AFRICA

evidence of peripheral artery disease.

Anticoagulation was started immediately with unfractionated

heparin (UFH), and the patient underwent surgical thrombectomy.

Fresh thrombi were obtained from both popliteal arteries at the

level of bifurcation via a femoral arterial incision (Fig. 1).

Anticoagulant therapy was continued with UFH for three days

and with low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at a dosage of

6 000 IU twice daily throughout his hospital stay.

He was discharged uneventfully on the fifth postoperative day

with LMWH treatment (enoxaparin 8 000 IU/day). He was doing

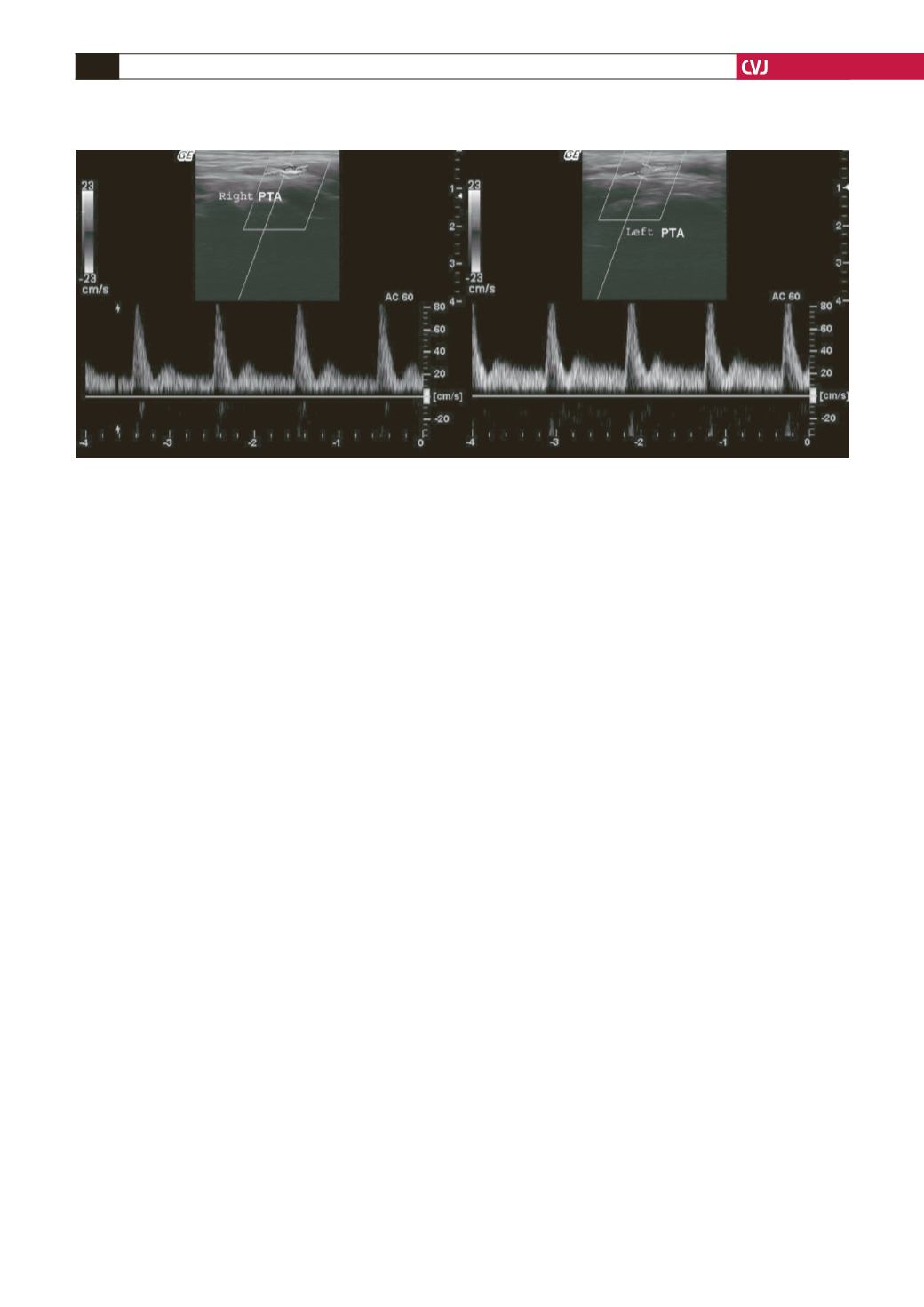

well at the first month’s postoperative follow up, with palpable

distal pulses, warm feet and three-phasic flow characteristics on

the Doppler control (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The incidence of thrombosis in malignancy is rapidly increasing.

Furthermore, malignancy is the second most common cause of

death in patients with peripheral arterial disease. In one study,

the incidence of clinical thrombosis in patients with cancer was

5–17% compared with 0.1% in the general population, most

of which are venous thrombosis.

4

In a recent study, Tsang

et

al.

reported a 3.8% incidence of arterial thrombosis in cancer

patients. Of the 419 patients with acute limb ischaemia, 16 had

associated cancer.

5

Despite many shared risk factors, the association between

arterial thrombosis and malignancies, and the pathogenesis of

thrombosis are not well understood. Goldenberg

et al

. reported an

increase in plasma levels of the thrombin–antithrombin complex

and prothrombin fragments 1 and 2, together with a significant

decrease in protein C activity in cancer patients.

6

Contributing

factors to thrombosis in malignancy include pro-coagulant

and cytokine release from damaged tumour cells, endothelial

damage caused by cytotoxic agents, and decreasing levels of

anticoagulants due to hepatotoxic effects of the chemotherapy

agents.

5

Up to 30 years ago, acute arterial embolismwas usually caused

by atrial fibrillation or mural thrombosis. The atherosclerotic

process is the most common cause of this phenomenon today.

7

However, Tsang

et al

. found that the development of arterial

thrombosis in cancer patients depended mainly on spontaneous

in situ

thrombosis in vessels without any pre-existing vascular

disease, rather than atherosclerosis or other structural vascular

problems.

5

They reported that histological examination of

the thromboembolic material derived from their subjects was

consistent with thromboembolism, and no tumour cells were

identified.

5

They concluded that nearly all acute ischaemic

events, as in our case, are the result of thromboembolus rather

than tumour emboli.

Arterial thrombosis is an uncommon adverse event

following chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil. In the literature

however, cisplatin was reported as the most common agent of

thromboembolism (8.4–17.6%).

5,8

In some individual case series,

different aetiological agents were referred to, such as bleomicin,

9

cyclophosphamide

4

or methotrexate.

5

When we examined these

studies, we noted that most used multiple chemotherapeutic

agents in combination, rather than one agent.

Heinrich

et al

. reported an aorto-bifemoral embolism

in an 18-year-old patient after cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil

chemotherapy, and treated it with discontinuation of the cisplatin

regimen.

8

However, in our patient, although he had been taking

both 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin, the oncologist considered

5-fluorouracil to be the causative agent of the thrombogenesis

and discontinued this agent. On LMWH treatment, there was

no evidence of thrombosis, and our patient had an almost

totally undamaged vascular wall and normal vascular flow

rate on Doppler ultrasonography. The exact mechanism of the

thrombosis triggered by 5-fluorouracil, however, is unclear.

Optimal management of cancer patients requires a strong

suspicion of an ischaemic event, concurrent with immediate

anticoagulation and surgical intervention. On the other hand, in

patients with acute arterial thrombosis without any history of or

risk factors for peripheral arterial disorder, screening for occult

malignancy should be considered.

5

Conclusion

We present an unusual case on the relationship between

combined chemotherapy and arterial thrombosis. Although there

are conflicting reports in the literature on the origins of thrombi,

combined chemotherapy regimens may be the causative factors.

However tumour-related release of pro-coagulants may also

Fig. 2. Doppler ultrasonographic data of the patient’s first month of follow up.