CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 4, July/August 2018

AFRICA

211

36.1% had valvular heart disease and 13.4% had left ventricular

diastolic dysfunction (HFpEF: EF

>

50%).

The duration of follow up of the 150 participants ranged from

five to 180 days. After a median follow up of 90.5 days, 42 deaths

(cumulative mortality rate of 28%) were recorded. Equivalent

figures were five deaths (cumulative incidence 45.5%) in mild PH,

nine deaths (cumulative incidence 20.5%) in moderate PH and

28 deaths (cumulative incidence 29.5%) in severe PH (

p

=

0.28).

Discussion

Our study aimed at determining the prevalence, clinical profile

and mortality rate from PH in a rural setting in sub-Saharan

Africa. We noted a high prevalence of PH, late presentation to

healthcare facilities in an advanced state of heart failure, and

consequently a high mortality rate at six months of follow up.

These findings could be attributed to the poor socio-economic

status, hyper-endemicity of risk factors for PH, and limited

availability of PH-specific drug therapies. In the PAPUCO

study,

7

which was a multinational study on the epidemiology of

PH in Africa with recruitment centres mostly in urban areas,

similar findings were noted. Therefore it can be said that PH still

presents a challenge on the African continent overall and not

only in the rural setting.

Our observed prevalence of 15.6% is higher than the

average of 10% prevalence observed in Australia in 2012 and

in other European countries.

13

This is somewhat to be expected

considering the high burden of risk factors such as rheumatic

heart disease, schistosomiasis, tuberculosis, sickle cell disease

and HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa, in addition to other

risk factors shared with high-income countries. In addition,

the SCC is located in a rural area that is difficult to access.

Therefore, patients are usually reluctant to visit the centre

until they are in advanced disease states or when referred by

cardiologists. A recent expert review on the global perspective

of the epidemiology of PH also supports our findings.

6

Among

the several co-morbidities assessed in our study population,

exposure to cooking fumes was the most common, especially in

women. This most likely results from the common practice in

Africa and Cameroon, particularly in the rural setting, where

women cook using open fires, unlike in high-income countries.

Systemic arterial hypertension was also common and in line with

studies from Africa,

7

USA

14,15

and Germany.

16

Hypertension is very common in sub-Saharan Africa where

it affects about 30% of the adult population, and mostly goes

undetected, undertreated and inadequately controlled.

17

It is the

principal cause of HF in sub-Saharan Africa. In the Pan-African

THESUS-HF registry of HF for instance, it was estimated that up

to 50% of HF cases were due to uncontrolled hypertension.

18

This

high prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension would most likely

also account for the high proportion of PHLHD in our study

population. With the growing epidemic of HF, LHD is now

globally recognised as the main cause of PH.

6,7,13

PHLHD was

dominated by patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction,

while PH due to rheumatic valvular heart disease is still common

in our setting.

The clinical presentation was dominated by exertion

dyspnoea, fatigue, cough and palpitations, which are common

and non-specific symptoms in most patients with cardiovascular

and/or respiratory conditions. Study participants were slightly

overweight with a mean BMI higher than observed in a study

in Nigeria,

19

but lower than reported in the USA.

15

Most of

our participants presented with moderate to severe functional

limitation, with 70% of them presenting in WHO FC or New

York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV.

These findings are similar to those in the PAPUCO study,

7

and

to those of Baptista and colleagues in Portugal in 2013,

20

who

observed that 71% of their patients presented in WHO FC III

and IV, as well as those of Fikret and colleagues in Germany.

16

This global observation of late presentation to medical attention

could be explained by the fact that most symptoms and signs of

PH are non-specific and therefore cases are usually misdiagnosed

in primary care until the later stages when patients seek specialist

care. Furthermore, in Africa, poor access to healthcare, limited

availability of diagnostic tools for PH, and the general reluctance

of patients in rural settings to seek medical attention until the later

stages of illness could explain at least in part the late presentation.

About a third of our patients died within the first six months

of being diagnosed with PH. This mortality rate is three times

higher than that observed in the USA

15

and the UK.

9

The high

mortality rate in our setting is most likely accounted for to some

extent by the unavailability of disease-specific drug therapies.

The fact that patients present at an advanced stage of the disease,

and their inability to comply with follow-up visits reflects to

some extent their limited financial coping capacity, resulting in

death in the absence of adequate care.

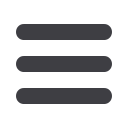

WHO FC

WHO FC I

WHO FC II

WHO FC III

WHO FC IV

Percentage

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

9.3

4.7

2.7

2.7

12

38.7

14.7

11.3

2

0.6 1.3 0

Mild PH

Moderate PH

Severe PH

Fig. 3.

Distribution of patients across WHO functional classes

and PH severity.

n

=

150

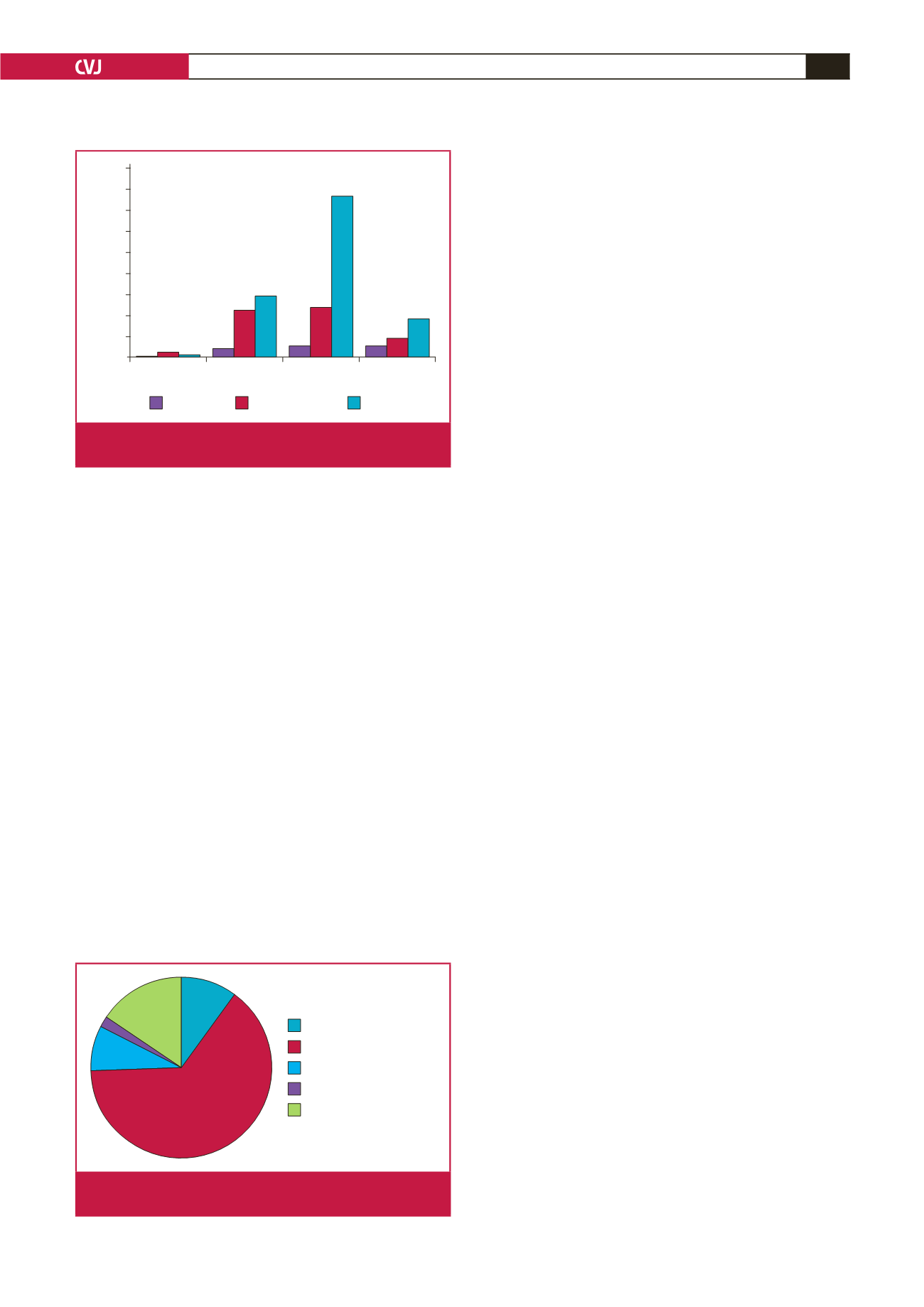

10%

64.7%

8%

15.3%

2%

Group 1 (PAH)

Group 2 (PHLHD)

Group 3 (PHLDH)

Group 4 (CTEPH)

Group 5 (PHUM)

Fig. 4.

Patient distribution according to the updated clinical

classification of PH.