CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 30, No 1, January/February 2019

AFRICA

17

in urban areas. All physicians reported adhering to dyslipidaemia

guidelines: 57.9% to ESC/EAS, 31.6% to ACC/AHA and 5.3%

to other international guidelines. In addition, 42.1% stated that

they adhered to the local South African guidelines, which are

closely aligned with the ESC/EAS guidelines. Statin intolerance

was defined as intolerance to one, two or three statins by 15.8,

47.4 and 36.8% of physicians, respectively.

Of 427 patients assessed, 31 were ineligible for enrolment

(Fig. 1). Therefore, the study population comprised 396

patients (mean

±

SD age, 60.0

±

10.2 years; 56.3% men) (Table

1). Patient demographic and clinical characteristics, lipid values

and LMTs are shown according to cardiovascular risk level in

Tables 1 and 2.

Overall, 36.4% were Caucasian/European, 24.7% were Asian

(including South Asian) and 24.2% were black African. Most

(

n

=

367, 92.7%) patients were from urban/suburban areas, and

81.1% (

n

=

317) had completed secondary education or higher.

A total of 279 (70.5%) patients had private medical insurance.

Most patients (81.8%) had healthcare cover (public or private)

that included drug reimbursement (private medical insurance) or

drug supply (public sector).

Most (87.1%) were overweight or obese [defined as a

body mass index (BMI) of 25 to

<

30 kg/m

2

and

≥

30 kg/

m

2

, respectively], 57.3% were physically inactive, 53.9% had

the metabolic syndrome (Adult Treatment Panel III), 13.4%

were current smokers and 22.0% reported regular alcohol

consumption. Diabetes mellitus was present in 65.2% and

hypertension in 81.3% of patients. A total of 135 (34.1%) patients

had documented CAD: previous acute coronary syndrome

(88/135, 65.2%), percutaneous coronary intervention (75/135,

55.6%) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (57/135, 42.2%).

Median time since dyslipidaemia diagnosis was 6.0

(interquartile range 3.0–12.0) years. The LDL-C value at the

time of first diagnosis was available in 130 (32.8%) patients;

mean untreated LDL-C was 3.9

±

1.4 mmol/l (151.7

±

52.7

mg/dl) and the LDL-C range was 0.7–9.0 mmol/l (27.0–347.5

mg/dl). At first diagnosis, 63.8% (83/130) of patients had an

LDL-C value

>

3.4 mmol/l (130 mg/dl) and 18.5% (24/130) had

LDL-C

>

4.9 mmol/l (190 mg/dl). Definite or probable familial

hypercholesterolaemia was reported in 6.2% of patients.

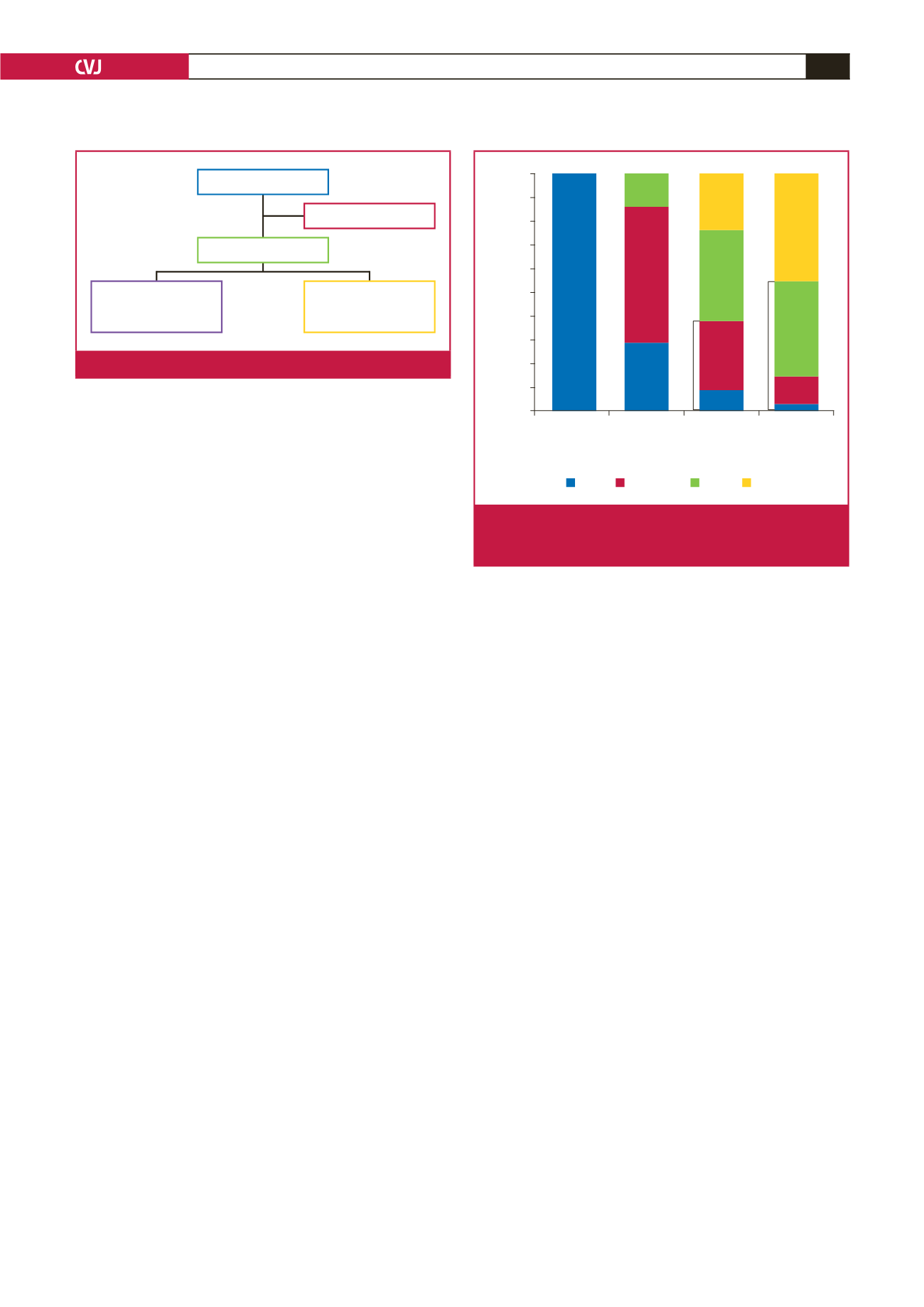

Of the 354 (89.4%) patients in whom SCORE cardiovascular

risk could be calculated, 63.0% were at very high risk, 34.7% at

high risk, 2.0% at moderate risk and 0.3% (one patient) was at low

risk. Physician-estimated risk correlated poorly with calculated

risk (Fig. 2); physicians underestimated risk in 54.7% of patients

at very high calculated risk and 38.2% of those at high risk.

Tables 3 and 4 show patient demographic and clinical

characteristics, lipid values and LMTs by patient ethnicity. A

smaller proportion of black African patients were male (35.4%)

compared with other ethnic groups (53.4–72.2%). In the black

African patient group, the incidences of obesity and hypertension

were 63.5 and 89.6%, respectively. Corresponding figures in the

other ethnic groups ranged from 32.7 to 54.2% for obesity and

71.5 to 87.9% for hypertension. Rates of documented CAD were

10.4% in black Africans compared with 28.6 to 50.0% in other

ethnic groups.

At study enrolment, 98.7% of patients were receiving statin

therapy; 90.7% were receiving statin monotherapy, 3.3% were

receiving statin plus a fibrate, and 2.6% were receiving a statin

plus a cholesterol-absorption inhibitor (Table 1). One-quarter of

patients treated with statins were receiving high-intensity statin

therapy (that is, atorvastatin 40 or 80 mg, or rosuvastatin 20 or

40 mg) and 17.7% were on the highest-dose regimen available in

South Africa at the time of the study.

Mean LDL-C value at enrolment was 2.6

±

1.0 mmol/l

(98.7

±

39.6 mg/dl) (Table 2). Overall, 41.4% of patients were

at or below their LDL-C target at enrolment (Figs 3A and 4).

Among patients for whom SCORE cardiovascular risk could

be assessed, achievement rates were 14.3, 59.3 and 32.3% for

those at moderate, high and very high risk, respectively (Fig.

3A). Around half of Asian (54.7%) and black African (53.2%)

patients achieved their LDL-C target compared with 29.8% of

European/Caucasian patients and 27.3% of patients of ‘other’

ethnicity (Fig. 3B); achievement rates ranged from 65.0% in

patients seen by physicians with several specialities to 6.3% in

patients under the care of a cardiologist (Fig. 3C).

Discussion

This observational study in patients on stable LMT indicated

that achievement of LDL-C goals in South Africa is inadequate,

427 patients screened

396 patients enrolled

354 (89.4%) patients

cardiovascular risk

assessable

42 (10.6%) patients

cardiovascular risk

not assessable

31 patients ineligible

Fig. 1.

Patient flow chart.

Calculated cardiovascular risk level (SCORE)

Low

(

n

=

1)

Moderate

(

n

=

7)

High

(

n

=

123)

Very high

(

n

=

223)

Physician-estimated cardiovascular risk (%)

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

28.6

8.9

29.3

57.1

38.2

14.2

23.6

45.3

40.4

38.2

Very high

High

54.7

11.7

2.7

Moderate

Low

Fig. 2.

Physician-estimated assessment of patient cardio-

vascular risk versus calculated risk (calculated using

SCORE

16

).